Legislatures in 12 states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government have enacted “second look” judicial review policies to allow judges to review sentences after a person has served a lengthy period of time.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, Incarceration, Racial Justice

Today, there are nearly two million people in American prisons and jails – a 500% increase over the last 50 years. 1 In 2020, over 200,000 people in U.S. prisons were serving life sentences – more people than were in prison with any sentence in 1970. 2 Nearly one-third of people serving life sentences are 55 or older, amounting to over 60,000 people. 3 People of color, particularly Black Americans, are represented at a higher rate among those serving lengthy and extreme sentences than among the total prison population. 4

Harsh sentencing policies, such as lengthy mandatory minimum sentences, have produced an aging prison population in the United States. 5 But research has established that lengthy sentences do not have a significant deterrent effect on crime and divert resources from effective public safety programs. 6 Most criminal careers are under 10 years, and as people age, they usually desist from crime. 6 Existing parole systems are ineffective at curtailing excessive sentences in most states, due to their highly discretionary nature, lack of due process and oversight, and lack of objective consideration standards. 8 Consequently, legislators and the courts are looking to judicial review as a more effective means to reconsider an incarcerated person’s sentence in order to assess their fitness to reenter society. 9 A judicial review mechanism also provides the opportunity to evaluate whether sentences imposed decades ago remain just under current sentencing policies and public sentiment. 10

Legislation authorizing judges to review sentences after a person has served a lengthy period of time has been referred to as a second-look law and more colloquially as “sentence review.” 11

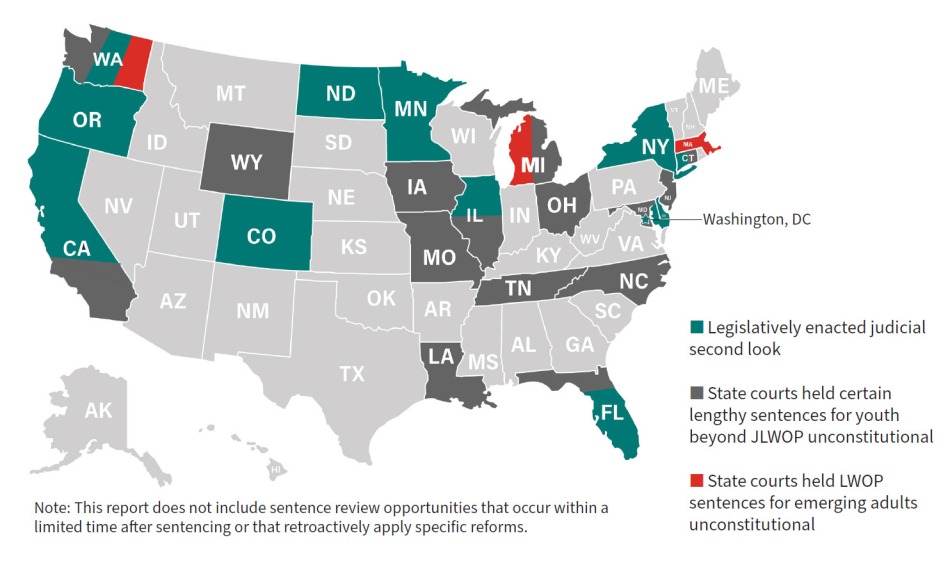

This report presents the evolution of the second look movement, which started with ensuring compliance with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions in Graham v. Florida (2010) and Miller v. Alabama (2012) on the constitutionality of juvenile life without parole (“JLWOP”) sentences. 12 This reform has more recently expanded to other types of sentences and populations, such as other excessive sentences imposed on youth, and emerging adults sentenced to life without parole (“LWOP”). Currently, legislatures in 12 states, 13 the District of Columbia, and the federal government have enacted a second look judicial review beyond opportunities provided to those with JLWOP sentences, and courts in at least 15 states determined that other lengthy sentences such as LWOP or term-of-years sentences were unconstitutional under Graham or Miller. 14

The report provides an overview of the second look laws passed by 12 state legislatures that provide judicial sentence review hearings beyond opportunities provided to those with JLWOP sentences – California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Washington – as well as the Council of the District of Columbia and the federal government.

In addition to legislative-driven judicial review reforms, litigation challenging extreme sentencing has created resentencing or earlier parole opportunities for people who were under 18 at the time of their offense serving excessive sentences other than JLWOP in at least 15 states – California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Ohio, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Tennessee, Washington, and Wyoming. These courts have found that sentences ranging between 40 years to 112 years are unconstitutional either under the U.S. Constitution and/or their respective state constitutions. 20 The Supreme Court of New Jersey created a sentence review mechanism for youth after serving 20 years.

Finally, courts in three states – Massachusetts, Michigan and Washington – have extended the Miller holding to emerging adults based on their state constitutions. The Supreme Court of Michigan held that mandatory LWOP was unconstitutional for those who were 18 at the time of the offense, and the Supreme Court of Washington held that mandatory LWOP was unconstitutional when imposed upon those who were 18, 19, or 20 at the time of the offense. 21 Most recently, the Supreme Court of Massachusetts held that LWOP (both discretionary and mandatory) is unconstitutional when imposed upon those under 21. 22

After a comprehensive review of the second look laws and appellate decisions interpreting those laws, The Sentencing Project recommends the following provisions be included in any second look law to ensure broad, fair, and meaningful application to the incarcerated:

This guidance builds on The Sentencing Project’s previous recommendations to include an automatic sentence review at 10 years and to monitor and address racial and other disparities in sentencing. 23

The Second Look Network: In response to the evolving second look movement, The Sentencing Project launched the Second Look Network in March 2023. The Network is composed of over 250 members representing 100 organizations, public defender offices, and law school clinics across the U.S. that provide direct legal representation to persons serving extreme sentences. The Network ensures that defense teams are connected, supported, and equipped to provide effective sentence review and parole representation. The Network also explores litigation strategies to expand second look opportunities.

The bulk of the second look movement began as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions in Graham v. Florida in 2010 and Miller v. Alabama in 2012. 12 In Graham, the Supreme Court held that a JLWOP sentence imposed for a non-homicide offense was unconstitutional because states must give youth a “meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.” 25 Since the death penalty was ruled unconstitutional for youth in Roper v. Simmons, then the next harshest penalty (LWOP) must be limited to the most serious category of crimes – homicides. 26

In Miller, the Supreme Court held that a mandatory JLWOP sentence for homicide constituted “cruel and unusual punishment” prohibited by the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Although Miller does not prohibit the subsequent imposition of life without parole for young people, a sentencing judge must take into consideration the mitigating and transient factors of youth – which came to be known as the “Miller factors” – and find that an individual is “permanently incorrigible” before imposing the most severe sentence of life without parole. 27 However, the Supreme Court changed course in Jones v. Mississippi (2021) and declined to require that a sentencing court make a finding on “permanent incorrigibility” before imposing the harshest penalty. 28

The Graham ruling applied to 123 incarcerated people. 29 Seventy-seven of them had been sentenced in Florida. 30 The Miller ruling, if applied retroactively, was poised to affect approximately 2,000 people serving sentences of mandatory JLWOP. 31 Four years later, the U.S. Supreme Court resolved the retroactivity issue in Montgomery v. Louisiana holding that Miller was fully retroactive. 32

Since these decisions, states have responded in different ways. While Alaska, 33 Kansas, 34 and Kentucky 35 had already prohibited JLWOP prior to the Miller decision, 25 additional states and the District of Columbia legislatively abolished the penalty of JLWOP post-Miller. 36 Supreme courts in Massachusetts, Iowa, and Washington held that JLWOP was unconstitutional under their state’s constitutions. 37

As set forth in Appendix 1, 19 states permit earlier and often more meaningful parole hearings for youth serving lengthy or life sentences, and four states permit earlier hearings for those ranging in age from 18 to 25 at the time of the offense. Additionally, several states, including California and Colorado, enacted laws providing for judicial resentencing opportunities for people serving JLWOP. 38

The Miller ruling dealt solely with the penalty of mandatory JLWOP imposed on a person for the crime of homicide, yet there have been legal challenges to extend Miller to other lengthy sentences imposed on those under age 18 at the time of the offense. For example, the Supreme Court of Illinois in 2019 held that a sentence of 40 years or more for homicide offenses imposed on a youth was a de facto life sentence and thus violated the Eighth Amendment. 39 To remedy this, the court sent the case back to the sentencing court to conduct a new sentencing hearing to consider the defendant’s youth and related characteristics. Other individuals with similar sentences may also petition the court for a resentencing hearing and a determination will be made whether they are also entitled to one if the Miller factors were not considered in their original sentencing hearing.

In 2022, the Supreme Court of Tennessee held that mandatory 60-year sentence for an individual under age 18 who was convicted of homicide, requiring at least 51 years of incarceration, was a de facto life sentence. 40 To remedy the constitutional violation, the court ordered that a parole hearing be held after serving between 25 years and 36 years, in which the individual’s youth and other circumstances would be considered. 41

Other states have also found lengthy homicide sentences for youth unconstitutional and sent the cases back to the sentencing courts for new sentencing hearings. Some of those states include: Missouri (life, with first parole hearing at 50 years), 42 Connecticut (50 year sentence without parole for a homicide offense, and a 100 year sentence for a homicide and non-homicide offense), 43 Wyoming (for sentences stacked consecutively, in which parole eligibility would be at 45 years, for homicide and other offenses). 44

The Graham ruling addressed the penalty of JLWOP and held that such sentences for non-homicide offenses were unconstitutional, as there must be a meaningful opportunity for release. Over the years, states have struck down other lengthy non-homicide sentences that amounted to de facto life without parole sentences. Some examples include: California (50 years to life for kidnapping and sexual offenses), 45 Maryland (four first-degree assault sentences totaling 100 years, with parole eligibility at 50 years), 46 Ohio (112 years for kidnapping, rape, and other offenses, with parole eligibility at 77 years), 47 Louisiana (99 year no parole sentence for armed robbery) 48 and Florida (56 year sentence for burglary and related offenses). 49 With the exception of Louisiana, all of these cases were sent back to the sentencing court for a resentencing to something less than the original sentence imposed, to reduce the amount of time before the individual becomes parole eligible. In Louisiana, the no-parole portion of the sentence was stricken so that the individual would become parole eligible at 25 years. 50

Arguments have expanded from reviewing excessive sentences for youth under the U.S. Constitution to reviewing the constitutionality of these sentences under state constitutions. Some states adopted the “cruel and unusual” language identical to the U.S. Constitution’s Eighth Amendment, while others have similar but slightly different language. 51

For example, the Supreme Court of North Carolina held that a sentence requiring a youth to serve 40 years or more violated North Carolina’s state constitution 52 that prohibits cruel or unusual punishment, which is “distinct from” and “broader than the set of punishments which are ‘cruel’ and ‘unusual.’” 53 The court also held that a sentence of life with parole eligibility after 50 years, violated the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. 54

Similarly, the Supreme Court of Michigan held that a life with parole sentence for second-degree murder for youth violated the Michigan state constitution’s prohibition against cruel or unusual punishment on the basis that its prohibition is broader than the U.S. Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Eighth Amendment. 55 The Supreme Court of Washington held that 46 years for first-degree murder constituted a de facto life sentence under both their state constitution and the U.S. constitution. 56 )

The New Jersey state constitution has a clause against cruel and unusual punishment. However, the Supreme Court of New Jersey held that the state constitution can “confer greater protection than the Eighth Amendment confers.” 57 Accordingly, under the state constitution, youth may now petition the court to review their sentence after 20 years. 58

The Supreme Court of Iowa has held that all mandatory minimum sentences imposed on youth are unconstitutional under the state constitution, 59 as well as a sentence of 50 years where the first parole hearing would be after 35 years. 60 )

Litigation has also been developing on whether emerging adults 61 – typically defined as those between the ages of 18 and 24 – should have the same type of mitigation considered for people 17 and younger before courts impose the most severe sentences. The general rationale for this argument is that young adults are still undergoing important cognitive, emotional, and psychological developments until their mid-20s. 62

The cases with the most notable impact have come from Washington, Michigan, and Massachusetts. In 2021, the Washington Supreme Court extended Miller protections to those under 21 years old who were sentenced to mandatory LWOP, based on the state’s constitution that prohibits “cruel punishment.” 63 The court held as follows:

There is no meaningful cognitive difference between 17-year-olds and many 18-year-olds. When it comes to Miller’s prohibition on mandatory LWOP sentences, there is no constitutional difference either. Just as courts must exercise discretion before sentencing a 17-year-old to die in prison, so must they exercise the same discretion when sentencing an 18-, 19-, or 20-year-old. 64

In 2021, the Michigan Supreme Court held that mandatory LWOP sentences for 18-year-olds convicted of first-degree murder violated the Michigan state constitution prohibition against “cruel or unusual punishment.” 65 More than 250 incarcerated people will have the opportunity to seek a new sentencing hearing. 66

In 2024, Massachusetts became the first state to ban the penalty of mandatory and discretionary LWOP for those under 21 years old, based on the state constitution’s ban on “cruel or unusual punishment.” 67

In 2017, the American Law Institute (ALI) – an independent organization composed of judges, lawyers, and law professors – recommended that states adopt a second look judicial sentence review process after 15 years of imprisonment. 68 Additionally, the ALI recommended a judicial review at 10 years for sentences imposed on youth 69 and a sentence review at any time for those experiencing “advanced age, physical or mental infirmity, exigent family circumstances, or other compelling reasons.” 70

In adopting the 10-year second look recommendation, the ALI stated:

[The second look recommendation] is rooted in the belief that governments should be especially cautious in the use of their powers when imposing penalties that deprive offenders of their liberty for a substantial portion of their adult lives. The provision reflects a profound sense of humility that ought to operate when punishments are imposed that will reach nearly a generation into the future, or longer still. A second-look mechanism is meant to ensure that these sanctions remain intelligible and justifiable at a point in time far distant from their original imposition. 10

In 2021, Fair and Just Prosecution, a network of local prosecutors, issued recommendations signed by over 60 current and former elected prosecutors and law enforcement leaders that included a sentence review for sentences after 15 years of incarceration for middle-aged and elderly incarcerated people. 72 Also in 2021, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) published its model second look legislation and recommended a judicial review of all sentences after 10 years of incarceration. 73

In 2022, the American Bar Association (ABA) adopted Resolution 502 that urged governments to enact legislation permitting courts to take a second look after 10 years of incarceration. 74 One year later, the ABA adopted a resolution recommending that governments adopt prosecutor-initiated resentencing legislation “that permits a court at any time to recall and resentence a person to a lesser sentence upon the recommendation of the prosecutor of the jurisdiction in which the person was sentenced.” 75

In 2022, the National Academies of Sciences recommended establishing second-look provisions as a way to reduce racial disparities in incarceration, given that racial disparities in imprisonment increase with sentence length. 76 In 2023, the Council on Criminal Justice’s Task Force on Long Sentences recommended that state legislatures, Congress, and policymakers consider “selecting opportunities for people serving long sentences to receive judicial second looks consistent with the purposes of sentencing.” 77

To support the growing movement for second look reform, in 2023 The Sentencing Project launched the Second Look Network – a professional network of post-conviction defense attorneys and mitigation specialists who provide direct legal representation to incarcerated individuals serving lengthy sentences. The Network is composed of over 100 organizations, public defender offices, and law school clinics dedicated to this work. The Network equips defenders with the latest research, news, and legal strategies to successfully bring more people who are serving lengthy prison sentences home. The goal of connecting defenders with each other is to create a community of impact to challenge mass incarceration. The Network is unique in its provision of this type of support to those practicing in the areas of sentence review, parole, compassionate release, and clemency.

In 2021, Connecticut enacted a second look law that is relatively broader than most other states with similar laws. 78 Persons convicted and sentenced after a trial, regardless of the length of their sentence or their age at the time of the offense, can petition the court to review the sentence. 79 The statute also allows the same review of the sentence if it was the result of a guilty plea resulting in a sentence of seven years or less. If the time required to be served was more than seven years, then the state’s attorney must agree to seek review of the sentence. 80 A 2022 revision to the statute clarified that it applies retroactively to all persons sentenced prior to the 2021 law. 81 However, the statute excludes all mandatory sentences from review, which cover approximately 70 crimes. 82

The sentencing court may, after a hearing and for good cause shown, reduce the sentence. 83 The “good cause” standard gives a court broad discretion in determining when a sentence should be reduced and does not require the consideration of any enumerated factors. 84 .))

The court also has discretion whether to hold a hearing. If a hearing is held, the following limitations of subsequent petitions will apply. If the motion is denied, another petition may not be filed until five years has elapsed. However, as of 2023, if the motion was granted in part (which generally means that the sentence was modified but not to the extent that the individual requested), then another petition may not be filed until three years has elapsed. 85 If the motion for a partial sentence reduction was granted in full, the petitioner must wait five years. 86 The right to counsel is not explicit in the statute; however, the public defender services statute provides that a public defender be appointed in “any criminal action,” 87 which has been broadly interpreted to mean “all” or “every.” 88

Salters at Yale Law School in 2023 for a panel discussion on life imprisonment and racial injustice.

Would justice have been better served if Gaylord Salters was required to serve his last six years in prison? That’s the question a judge in Connecticut was required to answer in 2022.

Salters was sentenced to serve 24 years for shooting two individuals at age 21, a conviction that he contests. At the time of the resentencing hearing, he had served 19 years and was 47 years old.

After a lengthy hearing, the judge found that Salters had established “good cause” to reduce his sentence and ordered his release. 89

In a book he published while in prison, Momma Bear, Salters presents a fictional story, which is a reflection of his own life experiences growing up in public housing during the crack cocaine era and his mother’s experience trying to protect her children. To make ends meet, he and his younger brother mowed lawns and shoveled snow. But when they became old enough to get a job, drugs hit the community where he lived and the jobs were gone. So they resorted to selling drugs.

It was perhaps those choices that caused police to focus on Salters when two men were shot. A significant piece of evidence was the testimony of one of the survivors, who identified Salters as the shooter. But in 2018, that survivor fully recanted and explained that he implicated Salters in order to avoid a mandatory prison sentence. 90

Salters with Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont in 2022 asking to commit funding for a Clean Slate implementation office that helps

clear lower-level felonies from people’s records.

Prison did not transform Salters’ thinking – he maintained his drive in spite of prison. “I knew what I had to do. They throw people away [in prison]. I was physically locked up. But I would never relinquish my mind.” 91 Salters had four children that he wanted to support while incarcerated. So he started his own publication company, Go Get It Publishing – and began publishing some of his writing. 92 The name Go Get It is his mission statement in life – “It’s up to you to put your best foot forward and do what you have to do in order to get to where you want to be. Period.” 93

When asked about the others he left behind, Salters explained that there are a lot of productive people in prison who have matured. “You can look at a person’s fingerprint in prison, you can look at their history . . . you can see the signs that are indicative of reform, because they stick out like a sore thumb . . . It’s not the prison. It’s the individual . . . Through that maturation, you will see a lot of individuals who are worthy of that second chance.

Salters credits an entrepreneurial education program run inside of the prison by a local college, Goodwin University, for providing him with support, education, and access to expert assistance to build his company. 94

In 2021, Connecticut passed a second look law allowing judges to modify sentences without the need for prosecutorial consent. This change opened the door for many, like Salters, to have a judge reconsider their sentences.

At the reconsideration hearing Salters’ son spoke on his father’s behalf: “The things that he has done even while being locked up has shown me how great of a father and a man he would have been if he hadn’t been locked up as well. I just know that with freedom, there is nothing but positive things that will come out of him being outside.” 95

Since leaving prison, Salters has become a staunch advocate against wrongful convictions and mass incarceration. 96 In 2023, the New Haven Independent announced Salters as its New Havener of the Year for his activism. 97 He is currently teaching a curriculum at a local Boys and Girls Club and wants to develop this program nationwide. He is also working with another local organization to uplift urban communities and is starting his own clothing line.

But for Connecticut’s second look law, Salters would still be in prison today. Typically, even people who are wrongfully convicted have few opportunities to challenge their conviction. Second look laws therefore also expand opportunities for releasing people who are innocent. Salters’ innocence claim does not appear to have affected the judge’s decision. Instead, the judge cited his good prison record, work and educational accomplishments, his publications, and his solid family relationships with his children. Both surviving victims supported his release.

When asked about the others he left behind, Salters explained that there are a lot of productive people in prison who have matured. “You can look at a person’s fingerprint in prison, you can look at their history . . . you can see the signs that are indicative of reform, because they stick out like a sore thumb . . . It’s not the prison. It’s the individual . . . Through that maturation, you will see a lot of individuals who are worthy of that second chance.” 91

As early as 1995, Oregon had a second look statute for youth who were convicted as adults to have a judicial review of their sentence after serving half of the sentence imposed. 99 Since that time, the statute has been amended multiple times. Most notably, in 2019, Oregon passed an omnibus criminal justice measure that abolished JLWOP, created new sentence limits for aggravated murder, developed an earlier parole review process for youth, and modified the judicial review of sentence process so it can occur after serving seven and a half years, or half of the sentence, whichever comes first. 100 However, all the 2019 changes are prospective and apply only to sentences imposed on or after January 1, 2020. 101 For all convictions that occurred prior to the 2019 revisions, the statute provides a sentence review for youth for offenses that occurred on or after June 30, 1995, and who received a sentence of at least two years and have served at least half of the sentence imposed. 102 Persons convicted of offenses that occurred prior to June 30, 1995, are ineligible to file a petition. There is an undecided issue of whether a life sentence is eligible for sentence review at the halfway mark of the mandatory term of 30 years. 103

The court is required to hold a hearing 104 and consider 13 enumerated factors. 105 The petitioner “has the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that the person has been rehabilitated and reformed, and if conditionally released, the person would not be a threat to the safety of the victim, the victim’s family or the community and that the person would comply with the release conditions.” 106 There is a right to counsel. 107 Either party can appeal the decision, but the issues that can be raised on appeal are limited to issues listed in the statute. 108

In 2013, Delaware abolished JLWOP and passed a retroactive sentence review mechanism for lengthy sentences imposed upon youth. 109

A person who was under age 18 at the time of the offense and who has served at least 30 years for first-degree murder or 20 years for any other offense may petition the court for a reduced sentence. 110 All mandatory sentences may be reduced. Additional petitions may be filed every five years; however, the court has the discretion to impose a longer wait period between reviews if there is “no reasonable likelihood that the interests of justice will require another hearing within five years.” The court will appoint counsel for an “indigent movant” only in the “exercise of discretion and for good cause shown.” 111 It is within the court’s discretion whether to permit a hearing on the motion. 112

In 2021, Maryland enacted the Juvenile Restoration Act that prohibits judges from imposing the penalty of JLWOP. It also provides that judges are not bound by mandatory penalties and permits persons convicted of offenses committed under the age of 18 and who have served at least 20 years for that conviction to file a request for sentence reduction. 113

The court is required to hold a hearing and consider multiple factors. The court may reduce the duration of a sentence if it determines that (1) the individual is not a danger to the public and (2) the interests of justice will be better served by a reduced sentence. The language “notwithstanding any other provision of law” grants broad discretion to a court, including reducing mandatory minimums. 114 It was not necessary to explicitly provide a right to counsel in this statute because Maryland is already required to provide legal representation at sentencing, resentencing, and modification hearings. 115 If the court denies or grants in part, a subsequent motion cannot be filed for at least three years. 116 A petitioner may not have more than three petitions considered. 117

As a result of this law, the Maryland Office of the Public Defender launched the Decarceration Initiative that was designed to provide public defender or pro bono counsel to all persons eligible to file a motion for reduction of sentence under the Juvenile Restoration Act. 118 During the first year of the Act, 36 hearings were held. In 23 of the cases, the courts imposed new sentences that resulted in release from prison. In four cases, the courts granted a reduction of sentence, but additional time in prison was required before release. The remaining nine were denied relief. 119

Although Florida has not banned the penalty of JLWOP, the state enacted a review of sentences for certain offenses that were committed by youth after they served 15, 20, or 25 years, depending on the conviction. 120 However, the statute applies to those offenses committed on or after July 1, 2014.

However, in 2015, the Florida Supreme Court held that the statute should apply retroactively to “all juvenile offenders whose sentences are unconstitutional under Miller.” 121 Since then, the Florida appellate courts have gone back and forth on which sentences are de facto life sentences warranting retroactive application of the statute. From 2017 to 2018, there were a number of decisions that held that a term-of-years sentence of more than 20 years warranted judicial review, 122 so all those cases were sent back to the sentencing courts to conduct a sentence review hearing. 123 However, in 2020, the Florida Supreme Court overturned those holdings and clarified a new standard – a young person’s sentence is not unconstitutional under Miller unless it meets the “threshold requirement of being a life sentence or the functional equivalent of a life sentence.” 124 Since that holding, the Florida appellate courts have determined that sentences over 30 years 125 and a life sentence with the possibility of parole after 25 years do not meet the threshold for review. 126 It is to be determined which sentences would warrant review under this new standard.

There is a right to counsel, 127 and the court must hold a hearing, consider several factors, and issue a written decision. 128 Mandatory minimum sentences may be reviewed. 129 If the court determines that the petitioner “has been rehabilitated and is reasonably believed to be fit to reenter society, the court shall modify the sentence and impose a term of probation of at least 5 years.” 130

Florida permits one review petition for nearly all offenses, except for youth who were sentenced to 20 years or more for a nonhomicide first-degree felony punishable up to a life sentence, in which case, they can have one subsequent review after 10 years. 131

In 2017, North Dakota abolished the penalty of JLWOP and enacted a reconsideration law for those whose offenses occurred prior to the age of 18 after serving at least 20 years for the offense. 132 Despite the statute being silent on the issue of retroactivity, the North Dakota Supreme Court held in 2019 that making the statute retroactive to offenses occurring before the effective date of the statute would infringe on the executive pardoning power. 133 Four years later, the same court reviewed the issue of retroactivity and further found that the legislature did not intend for the statute to be applied retroactively. 134

When hearings are eventually held on these motions – presumably on or after the year 2037 (approximately 20 years after effective date of statute, when someone would become eligible to file) – courts shall consider a number of enumerated factors and may modify the sentencing, having “determined the defendant is not a danger to the safety of any other individual, and the interests of justice warrant a sentence modification.” 135 Up to three requests for modification can be made no earlier than five years between each decision. 136 The statute is silent as to whether a court must hold a sentence review hearing before making a ruling and whether there is a right to counsel.

New Jersey is the only state whose highest court was responsible for creating a new judicial review mechanism, as opposed to the legislature. In 2022, the Supreme Court of New Jersey held that certain mandatory sentences imposed on youth violate the state’s constitution. 137 Concerned about waiting for the legislature to act to remedy the issue, the court then declared that youthful defendants may petition the court to review their sentence after serving 20 years. 138 Because there is no statute, there is little guidance on the sentence review process, except that resentencing courts should apply the Miller factors.

The District of Columbia currently has the most expansive age-based second look judicial review statute in the country. The second look law permits an individual to file a reconsideration of sentence if the offense occurred before the individual’s 25th birthday and after 15 years of imprisonment. 139

The initial version of the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act (IRAA), effective in 2017, provided second look hearings for youth convicted as adults for offenses committed before age 18 and after serving 20 years, who have not yet become eligible for release on parole. 140 But in 2018, the law was amended to reduce the time required to be served from 20 years to 15 years, and struck the provision regarding parole eligibility. 141 It also removed “the nature of the offense” from the factors a court should consider. This change was made in response to the U.S. Attorney’s practice of citing the seriousness of the offense as the basis to deny the motion. 142 ) The Omnibus Public Safety and Justice Act of 2020 increased the age eligibility from under 18 to under 25. 143 . See also DC Corrections Information Council (2021, May 19). DC Council Passes Second Look Amendment Act of 2019 [Press release].))

The court may reduce the sentence after considering multiple factors 144 and finding that “the defendant is not a danger to the safety of any person or the community and that the interests of justice warrant a sentence modification.” 145 The court may also reduce a mandatory sentence. 146 A petitioner has three opportunities to pursue an application for sentence review whether the previous petitions were granted or denied, and may apply three years after the last petition. 147 The statute applies retroactively to all prior convictions. 148 The court is required to hold a hearing 149 and issue a written decision. 150 The petitioner is entitled to counsel. 149

The DC-based Second Look Project has reported that in the six years following IRAA’s enactment in 2017, “approximately 170 people have been released from extreme sentences.” 152 When DC expanded its law to include emerging adults up to age 25 in 2021, over 500 people gained an opportunity for release from such sentences. 153

When asked about his favorite childhood memory, Randall McNeil described the times he would visit family in Charlotte, NC and would watch kites flying in an open field. Having grown up in Northeast Washington DC, he had never seen anything like it, and he was instantly captivated. McNeil spent most of his summers looking forward to seeing those colorful kites in the sky.

At the young age of 16, McNeil lost his mother – his primary guardian – and the person that knew and understood him best. A year later, McNeil lost his grandmother and became a father for the first time. McNeil had two more children in the subsequent years.

When McNeil was 20 years old, he was found guilty of multiple charges involving an armed robbery and kidnapping. McNeil was sentenced to 66 years and spent the next 24 years of his life incarcerated at various state and federal institutions before his release from Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) in Cumberland, MD.

As McNeil did his time, he was determined to become the best version of himself in hopes that he would someday be given the opportunity to show the world that despite what he did, he was worthy of redemption. Prior to his incarceration, McNeil earned his GED and recalled that in 2003 while in prison, his perspective about being incarcerated shifted when he began to frequent the prison law library. He described those visits as “going to find the key” to his redemption. 154 It was his source of hope.

He also discovered his ability to positively influence those incarcerated with him. McNeil worked to help shift the mindsets of the men inside and learned that he had a desire to instill hope and value in others despite their circumstances. He went on to become a qualified member of the prison suicide watch team.

McNeil understood that for others to see him as the person he knew himself to be, he would have to constantly put himself in positions to show up as that person. During his time at FCI Cumberland, McNeil worked for Unicor Sign Factory where he was started in a position inputting and receiving orders on a computer. Due to his perseverance and determination, McNeil was quickly promoted to a supervisor.

With the expansion of the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act (IRAA) in 2020, McNeil was finally given an opportunity to petition for his freedom. McNeil was an exemplary candidate. In August 2022, McNeil was granted his freedom with the caveat of five years’ probation—a decision that McNeil desires to have reconsidered. Upon his release, he was finally able to marry Donnetta, the mother of his children, on Valentine’s Day of 2023.

McNeil is grateful to his daughter for providing him with a home in the District of Columbia, one of the requirements for him to be released. He also credits two reentry programs, BreakFree Education and Free Minds Book Club, for helping provide job opportunities and a welcoming community. Through BreakFree Education, McNeil was able to apply for a fellowship at Arnold Ventures, where he is now a full-time employee. His proudest moment has been helping to fund a newly launched nonprofit organization led by another formerly incarcerated person.

McNeil, his daughter Randaisha, and his granddaughters Logan and Dior.

McNeil was not naïve enough to believe that coming home would be easy, but he is honest enough to admit that he did not anticipate just how complex familial and friendship dynamics could be. Free Minds has been an essential part of his life, enabling him to meet weekly with other formerly incarcerated men locally, where they can discuss the challenges of societal reintegration.

When asked about those still incarcerated, he said, “There are a lot of Randalls in there. They all need a second chance. Many of them were arrested after 25.” 155

Enacted in 2018, the First Step Act (FSA) is a bipartisan law that included a wide range of criminal justice reforms in the federal system. 156 One reform was to the law governing the reduction in sentence authority, commonly referred to as “compassionate release.” The FSA amended the law to allow incarcerated people to file compassionate release motions on their own behalf in court. 157 Prior to this reform, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) had the sole authority to recommend release to a court. The BOP rarely recommended compassionate release. 158

Now, people serving federal prison sentences can file these motions themselves after giving the BOP 30 days to make this recommendation. In the fiscal year 2020, 96% of those granted relief filed their own motion. 159

In addition to Congress’s change to the compassionate release process, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which is responsible for describing in a policy statement what are extraordinary and compelling reasons for compassionate release, expanded the list in 2023. The prior reasons were limited to medical, geriatric, and extreme family circumstances. 160 Now, additional circumstances include, among others, (1) sexual assault at the hands of BOP personnel; (2) an unusually long sentence in which an intervening change in the law has resulted in a gross disparity between the sentence being served and the sentence that could be imposed today; and (3) any other circumstances or combination of circumstances that are similar in gravity to the listed grounds. 161 There are no exclusions based on the nature of the criminal conviction or length of sentence. No one sentenced prior to 1987 is eligible, whether they are serving a parolable or non-parolable sentence. 162

There is no right to counsel on these motions; however, a collaborative effort between the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL), FAMM, and the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs has created a clearinghouse program to identify individuals who may qualify for compassionate release and to recruit, train, and support legal pro bono counsel to represent them. 163

From October 2019 through September 2023, 31,069 compassionate release motions were filed. 164 Of those filed, 4,952 (16%) were granted, and 26,117 (84%) were denied. 165 COVID-19 accelerated use of this law, with most grants of relief (95%) during this period occurring in the second half of the fiscal year 2020. 166 Courts cited the risk of contracting COVID-19 as at least one reason to grant the motion in 72% of the motions granted that fiscal year. 166 However, since its peak in October 2020 with approximately 2,000 decisions recorded that month, filings have steadily decreased with only about 147 decisions recorded in September, 2023. 168

In 2020, the Council of the District of Columbia enacted an emergency COVID-19 response bill, which permitted incarcerated individuals to seek compassionate release from the courts. 169 In 2021, the law was made permanent. Eligibility includes those who are 60 years old and older who have served at least 20 years, those with a terminal illness, or who otherwise present “extraordinary and compelling reasons” that warrant a sentence modification. 170 No other state has a similar judicial sentence review provision based only on elderly age and number of years served.

The court may reduce a sentence if it determines the petitioner “is not a danger to the safety of any other person or the community.” 171 The court must consider approximately 11 outlined factors, but it may not consider factors that have no relevance to present or future dangerousness (e.g., the need for just punishment or general deterrence). 172 .)) The defendant has the burden of proof by a preponderance of the evidence. 173

Mandatory minimums may be modified. 174 Motions may be filed by the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, the Bureau of Prisons, the United States Parole Commission, or the defendant. 175 As a matter of practice, counsel is routinely provided. 176 The court is not required to hold a hearing to grant or deny a motion. 177

The District of Columbia Corrections Information Council last reported that from March 2020 through March 16, 2021, 143 individuals were granted compassionate release. 178

Incarcerated people, particularly women, commonly report histories of family or intimate partner violence. Courts typically do not account for when those experiences influence their involvement in crime. 179 A new type of second look law has emerged that focuses on reducing the sentences of these survivors when their victimization was a significant contributing factor to the offense.

New York enacted legislation in 2019 that allows intimate partner and family violence survivors to petition the court for sentence review that is fully retroactive. 180 Most recently in 2024, Oklahoma nearly enacted a similar measure in 2024. 181 In 2016, Illinois enacted a similar law; however, the law includes a two-year statute of limitations to file the petition from the date of conviction, and the law is not retroactive to prior convictions, essentially leaving no remedy for individuals sentenced prior to 2014. 182 Advocates have criticized the lack of meaningful impact of this law. 183 Policymakers in Louisiana, Oregon, and Minnesota have introduced similar reforms. 184

In New York, a survivor who was sentenced to a minimum or determinate sentence of eight years or more prior to the enactment date of the law may petition for sentence review. 180 Individuals sentenced after the law’s enactment are not eligible for sentence review but can receive a lower sentence if they otherwise qualify for relief. The statute applies to those who are incarcerated or on community supervision but excludes certain crimes, such as aggravated murder, first-degree murder, or any offense that requires an individual to register as having committed a crime of a sexual nature. 186

The request for sentence review must include “at least two pieces of evidence corroborating the applicant’s claim that he or she was, at the time of the offense, a victim of domestic violence.” 187 If the evidence is submitted with the application, the court is required to hold a hearing. A survivor must demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence 188 that at the time of the offense (1) they experienced “substantial physical, sexual, or psychological abuse,” (2) the abuse was a “significant contributing factor to the criminal behavior,” and (3) the sentence imposed in the absence of this mitigation is “unduly harsh.” 189 Interestingly, reviewing appellate courts have the authority and discretion to impose a new sentence if they disagree with the sentencing court’s decision. 190

As of February 2024, 58 people have been resentenced. 191

In 2018, California passed a law affecting U.S. military veterans and current U.S. service members who are serving sentences for felony convictions. 192 The law allows qualifying individuals to petition for a recall of sentence and request resentencing if they “may be suffering” 193 from “sexual trauma, traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, or mental health problems as a result of the defendant’s military service,” 194 if not previously considered at the time of sentencing. 195 The court may reduce the term of imprisonment by modifying the sentence “in the interest of justice.” 196

Individuals convicted after trial, as well as through plea agreements, are eligible to petition for a recall of sentence and request resentencing. 197 The statute applies retroactively. 198

Not all veterans are eligible to seek relief under this provision – exclusions include those convicted of any serious or violent felony punishable by life imprisonment or death. 199 Because of the statute exclusions, only those serving determinate sentences (a set amount of time to serve) are eligible to seek relief. 200 Approximately 33% of people incarcerated in California are serving indeterminate sentences. 201 The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that in 2016, 8% of all people in state prisons were veterans. 202

In 2023, Colorado enacted a judicial modification opportunity for those convicted under the habitual offender laws who have been sentenced to 24 years or more, and have served at least 10 years, but it applies only to offenses that occur on or after 7/1/2023 (see at Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-1.3-801). Therefore, nobody will be able to apply for a sentence modification until 2033, at the earliest. If the court approves a sentence modification, the new law authorizes the court to resentence the petitioner to a term of at least the midpoint in the aggravated range for the class of felony for which the defendant was convicted, up to a term less than the current sentence. A petition is entitled to appointed counsel and a hearing.

California’s original recall and resentencing law allowed district attorneys (see Prosecutor-Initiated Resentencing section, below) and the Secretary of the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (“corrections”) to file a petition at any time to recommend a reduced sentence for an individual. 18 Effective January 1, 2024, this law was expanded to permit judges to initiate resentencing proceedings if there was a change in the law, which applies to many cases. 204 Incarcerated people do not have the authority under this law to file a petition requesting resentencing – it must be made by the judge, district attorney, or someone from corrections.

When a recall is initiated by a district attorney or a corrections official, “there shall be a presumption favoring recall and resentencing,” which can only be overcome if a court finds the individual currently poses an unreasonable risk of danger to public safety as defined by statute. 205

Whether initiated by the judge, district attorney, or corrections, the court is required to apply any new sentencing rules or changes in the law that reduced sentences “so as to eliminate disparity of sentences and to prompt uniformity of sentencing.” 206 In addition, the court could consider other factors, such as age, time served, diminished physical condition, defendant’s risk for future violence, and evidence that the circumstances have changed so that continued incarceration is “no longer in the interest of justice.” 207 The court is required to consider these additional factors: psychological, physical or childhood trauma, abuse, neglect, intimate partner violence, human trafficking, and whether the person was under the age of 26 at the time of the offense. 207

All felony offenses may be considered for reconsideration, and at any time. Also, the court previously could, but is now required, to consider post-conviction factors, such as age, disciplinary record, record of rehabilitation, physical condition, etc. The court must determine whether these circumstances have changed so that “continued incarceration is no longer in the interest of justice.” 207

There has been a recent movement in prosecutor offices to proactively look back at sentences of people still incarcerated after they have served a significant time period in order to determine if the sentence, under today’s standards, was unduly harsh, stemmed from outdated practices and policies, or no longer serves the interest of justice. 210 The nonprofit organization For The People, touts that prosecutor-initiated resentencing (PIR) is a “powerful tool to help repair the damage” of the disproportionate incarceration of Black and Brown people.” 211

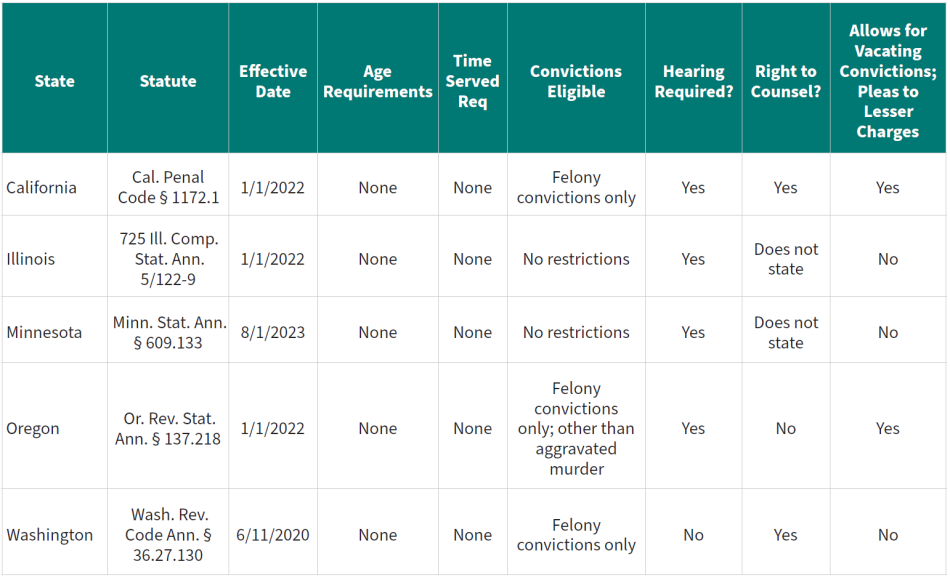

In 2018, California enacted the nation’s first PIR law that allows prosecutors to petition the court for a reduction of sentence for those with felony convictions. 212 As of 2024, four other states – Washington, Oregon, Illinois, and Minnesota – have PIR laws. 213 In the past three years, PIR legislation has been introduced in seven other states – Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Utah, and Texas. 214 In 2023, the American Bar Association adopted a resolution recommending that all states and the federal government adopt prosecutor-initiated resentencing legislation “that permits a court at any time to recall and resentence a person to a lesser sentence upon the recommendation of the prosecutor of the jurisdiction in which the person was sentenced.” 75

At the end of 2023, over 900 people have been resentenced as a result of PIR. 216 Only two of these resentencings occurred in Illinois. 217 Of those 900, over 400 were released from California alone and the remaining 500 from other states. 218

In passing PIR, the California Legislature declared that the purpose of sentencing is “public safety achieved through punishment, rehabilitation, and restorative justice.” 219 This same intent was echoed by the Washington and Illinois state legislatures 220 and both provided this same additional rationale: “By providing a means to reevaluate a sentence after some time has passed, the legislature intends to provide the prosecutor and the court with another tool to ensure that these purposes are achieved.” 221

In 2023, the Louisiana Supreme Court struck down a statute that allowed a district attorney and petitioner to jointly enter into any post-conviction plea agreement to amend a conviction or sentence with the approval of the court. The majority wrote that the law unconstitutionally allowed a judge to reverse a conviction “merely because the defendant and the district attorney jointly requested the court do so.” 222 The law lacked guardrails requiring the finding of a legal defect. However, the majority emphasized that the opinion did not prevent resentencing from continuing under Louisiana’s remaining post-conviction statute. The Court recognized that a prosecutor must have discretion to join an application for post-conviction relief because of their “responsibility as a minister of justice . . . to achieve the ends of justice.” 222

Based on the differences in the various second look laws in Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Florida, Maryland, Oregon, and North Dakota, as well as the resulting appellate holdings interpreting the statutes, there are a number of issues that advocates and legislators should consider to allow for a meaningful review and to avoid inconsistent application, confusion, or future litigation.

The majority of the second look laws passed apply to incarcerated people who were under age 18 at the time of the offense and have served at least 15 to 20 years. In order to more effectively tackle extreme sentences, all other age groups and all convictions should also be granted sentence reviews.

Evidence suggests that most criminal careers are under 10 years, and as people age, they usually desist from crime. 6 Even people who engage in chronic, repeat offenses that begin in young adulthood usually desist by their late 30s. 6 A robust body of empirical literature shows that people released after decades of imprisonment, including for murder, have low recidivism rates. 226 Moreover, recidivism rates are lowest among those convicted of the most serious violent crimes for which people generally serve the longest sentences – sexual offenses and homicide. 227

Additionally, despite the clear evidence that persons 60 and over are unlikely to commit any new offenses, only two jurisdictions – the District of Columbia and the federal government – have compassionate release laws for the elderly population where there does not need to be a serious or terminal medical condition, and there are no crimes that are excluded from review. 228 Wisconsin provides a judicial review of sentences for those ages 60 and over, however, a Program Review Committee must unanimously agree to refer the petition to the sentencing court. Additionally, the statute excludes those serving felonies, resulting in the process rarely being used. 229

As set forth in Appendix 2, states with elder parole provisions based on age alone often have felony or crimes of violence exclusions, leaving parole eligibility to those serving misdemeanors or non-violent offenses. Of the 13 states with elder parole, only four states – Georgia, South Dakota, Utah, and Washington – do not have felony or crime of violence offense exclusions. However, the number of people being released in these states is concerningly low. 230

Most other states have some version of court or parole board compassionate release for those with serious medical conditions or terminal illnesses, 231 but the process and impact has been criticized, and the vast majority of states earned failing grades by FAMM. 232

When statutes do not directly address the issue of whether a second look provision is retroactive or prospective, the result can be appellate litigation and confusion. For example, the question of whether North Dakota’s second look statute applied retroactively resulted in two North Dakota Supreme Court decisions in a four-year period. 233 The Court held, on different grounds, that the statute was not retroactive. 234 Oregon’s second look statute has both retroactive and prospective-only sections that have the potential to create confusion. 235

The issue of retroactivity is perhaps the single-most important issue to include in a second look law because the number of eligible persons will vary significantly. Currently, the youth second look laws in North Dakota and Florida (with a Miller exception) and Illinois’s Domestic Violence Act are not retroactive.

In order to have a more immediate and substantial impact to end mass incarceration, accelerate racial justice, and better invest in public safety, all provisions should expressly apply retroactively. This recommendation also aligns with growing evidence that limiting maximum prison terms to 20 years, except in rare cases, also achieves the same goals. 236 Full retroactivity allows for an equitable review for all persons serving disparate sentences for the same offenses, regardless of when the offense was committed.

Mandatory Sentences: Significant racial disparities exist in the application of mandatory sentences and accordingly, courts should be vested with sentence review authority to remedy unfair and racially-disparate mandatory sentences. 237 For states with mandatory sentencing, there is a potential issue of whether the court has the authority to reduce those sentences. 238 The second look statutes in Oregon, North Dakota, and the District of Columbia are silent on the issue, whereas Connecticut explicitly states that mandatory sentences cannot be reduced, and Florida and Delaware state that they can be reduced.

Plea Agreement Sentences: In cases where all parties agree to a sentence (typically referred to as binding plea or negotiated pleas), there is a question as to whether a court can later modify that sentence without state consent. For example, in Maryland, the ability to reduce the sentence of a binding plea was not clarified until the issue was appealed regarding a different sentence review statute interpreting the same statutory language. 239 Clarifying the court’s authority over these types of arrangements is important and it is recommended that courts have the ultimate discretion in determining whether a sentence imposed years prior remains fair and equitable.

To avoid uncertainty and future litigation, as well as provide incarcerated people meaningful opportunities to improve, sentence reviews should occur through the remainder of the sentence at regular interviews, or at least, three times. Additionally, The Sentencing Project recommends that hearings occur at 10 years and subsequent hearings occur within a maximum of two years. 240

Four jurisdictions – Maryland, the District of Columbia (for emerging adults), Florida, and North Dakota – have petition limits and time limits between petitions. 241 Connecticut and the District of Columbia (compassionate release) have no stated petition limit, so it is presumably limitless. Oregon is silent on the issue on the number of petitions and intervals. However, Oregon’s process is initiated by the Oregon Youth Authority or the Department of Corrections when the petitioner becomes eligible for review, so it presumably permits only one hearing.

Although it is well-settled that there is a right to appointed counsel at initial sentencing hearings, 242 states diverge generally on whether there is a right to counsel when sentences are subsequently reviewed. 243 In the context of second look reviews, nearly all jurisdictions provide the right to counsel at those hearings, and that right cannot be understated.

Counsel is critical in effectively presenting evidence of rehabilitation and accountability to the court through records and witnesses, thus ensuring fairness and transparency throughout the process and assisting with reentry planning. The National Association for Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) explains:

Counsel is needed to ensure the most effective and focused presentation of the relevant issues, avoiding extraneous details, investigating and uncovering relevant ones, and giving voice to the applicant’s remorse and vision for their future. In particular, many petitioners will suffer from mental illness or intellectual disabilities that would prevent them from being able to meaningfully represent themselves in court. And, advocating for one’s self from a prison is an extraordinarily difficult task, if not impossible. 244

However, that right is not triggered in some jurisdictions until the petitioner files a petition for a sentence review in court. If that is the established process to initiate proceedings, then it is important to ensure that counsel is able to freely amend or supplement the motion and be able to submit relevant documents. Therefore, in order to ensure counsel’s responsibility to provide effective representation, it is recommended that language be included that “counsel has the right to freely amend and supplement any written materials, and submit relevant documentation, at any time prior to the hearing.”

Without a requirement for a hearing, courts may deny petitions based solely on what is written in the petition. That outcome is even more problematic if there is not a right to counsel on the petition and the courts are relying on pro se mitigation alone. Therefore, courts should be required to hold hearings that would allow the petitioner and counsel to fairly present evidence, records, and witness testimony in order to satisfy the required burden for a reduction in sentence.

Four jurisdictions – the District of Columbia (emerging adults), Florida, Maryland, and Oregon – require a court to hold a hearing on a sentence review motion. Delaware, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia (compassionate release) do not require the court to hold a hearing. North Dakota’s statute is silent.

Most states have provided the courts with a number of factors they should consider when determining whether a sentence reduction is warranted, including a general catch-all provision that allows the courts to also consider any other factor it deems appropriate. Connecticut and the District of Columbia’s geriatric laws are the exceptions, likely because neither statute was in response to the Miller decision.

In Connecticut, a “good cause” standard is to be applied, giving the court broad discretion in what factors to consider when determining whether a sentence should be reduced. 245 .)) In the District of Columbia, additional litigation provided the sentencing court with this guidance: it is the petitioner’s burden to establish that they are non-dangerous by a preponderance of the evidence pursuant to compassionate release statute. 246

It is recommended that factors, as well as a catchall provision, be included to give courts appropriate guidance for consideration and to minimize future litigation. Sentence review laws for youth and emerging adults should consider, at a minimum, including the Miller factors and the latest data regarding neuroscience to ensure an appropriate constitutional review of the sentence based on data. 247

Other recommended factors include: (1) evidence of level of involvement and the ages and influence of other participants; (2) whether the individual has substantially complied with the rules of the institution; (3) work history and completion of educational, vocational, or other programs; (4) the individual’s family and community circumstances at the time of the offense, including any history of trauma, abuse, or involvement in the child welfare system; (5) statements of witnesses regarding evidence of maturation and rehabilitation, including family, friends, medical professionals, and correctional professionals; and (6) physical and mental health records.

Including a consideration for a person to admit guilt or demonstrate remorse can be problematic. This requirement limits the use of second look mechanisms for people who are wrongfully convicted. Moreover, research suggests that expressions of remorse are not correlated with reduced recidivism and their assessment is impacted by racial bias. 248

Evidence should also be considered when state prisons lack sufficient due process and oversight on the issuance of infractions, as well as lack of consistent guidelines regarding length and level of punishment; the lack of prison programming opportunities; and the inability in some prison systems to matriculate to lower levels of security based solely on seriousness of the charge and not rehabilitative efforts or security risk. 249

In order to ensure that all relevant factors are considered and to provide appellate courts with a sufficient record to determine whether the sentencing court abused its discretion, a written decision – or in the very least an oral decision addressing all the reasons for the court’s decision – should be required. Only four jurisdictions – the District of Columbia (emerging adults), Florida, Maryland, and Oregon – require the reviewing court to issue a written opinion stating the reasons for granting or denying the petition.

Some jurisdictions – Connecticut, the District of Columbia (emerging adults), Florida, Maryland, and North Dakota – include sections directly in the sentence review statute that require the court to consider crime survivor impact statements as a factor in their overall consideration. Florida also includes a provision that if the victim or next of kin chooses not to participate, the court may consider previous victim impact statements made during the trial, sentencing, or other sentence review hearings.

Codifying the importance of victim impact statements, as well as any other rights provided in the state’s respective victim bill of rights, is recommended to ensure compliance. Victims cannot be expected to shed light on reoffending risk, given their limited contact with the incarcerated individual. 250 But involving crime survivors in these hearings also provides an opportunity to direct victims to resources and restorative justice programs, as needed, to give them, as The Sentencing Project has noted, “more active role in their recovery beyond testifying and submitting impact statements.” 251

The implementation of second look laws may create confusion regarding the role of the parole board versus the role of the court. For example, in Maryland, a court denied a petitioner’s second look motion and stated that it was a parole board’s decision whether to release the petitioner from incarceration, “not the court’s decision.” 252 The appellate court remanded the case back for resentencing and held that petitioner’s parole eligibility “did not impair his right to be considered for a sentence reduction by the circuit court” and that the court committed an error of law by deferring to the parole board. 253

The limited effectiveness of parole boards in releasing rehabilitated citizens, as well as concerns with the lack of due process and oversight, among other issues, has fueled the need for broader judicial sentence reviews. The due process protections that judicial review hearings afford, such as a transparent and public process with adversarial testing and appellate review, can provide a much more meaningful hearing. 254 The Model Penal Code explained that creating a second look provision in part “grew out of disillusionment with traditional arrangements of back-end discretion over the lengths of prison terms, which place large reservoirs of power in parole agencies and corrections officials.” 255

Therefore, it is recommended to provide clear guidance in the bill’s description or text to courts regarding their discretion and authority, regardless of parole eligibility or prior board decisions.

In addition to the recommendations above, legislators and advocates should also consider previously published second look law guidance that highlights many other issues, including the following:

There is also guidance specific to Domestic Violence Survivor Justice Act model legislation by The Sentencing Project and Survivors Justice Project, as well as prosecutor-initiated resentencing model legislation by For the People. 260

The second look movement started with the seminal holdings in Graham v. Florida and Miller v. Alabama. States reacted differently in order to implement these holdings, including enacting new second look laws for youth, as well as creating earlier parole opportunities for youth serving lengthy or life sentences. Those states that enacted earlier parole opportunities are listed here.

Elder parole opportunities, in the states that have special provisions for this population, are extremely limited and ineffective, which necessitates the need for robust second look laws everywhere. Fourteen states allow for parole consideration based on advanced age; however, only four states – Georgia, South Dakota, Utah and Washington, do not have felony or crime of violence offense exclusions. However, the number of people being released in these states is concerningly low. 261 All states, with the exception of Texas and Virginia, have earned at least a D rating for their geriatric parole policies. 262 Click here to view the list.

Not included in this section are parole opportunities based on advanced age and having a serious medical condition. For a list of medical parole statutes, please see The Sentencing Project’s Nothing But Time 263 and FAMM’s Compassionate Release State by State. 264

Nellis, A. (2023). Mass Incarceration Trends. The Sentencing Project.

Nellis (2023), see note 1.

Nellis, A. (2021). No End in Sight: America’s Enduring Reliance on Life Imprisonment. The Sentencing Project; see also Ghandnoosh, N. (2023). Ending 50 Years of Mass Incarceration: Urgent Reform Needed to Protect Future Generations, p. 4. The Sentencing Project. (The population serving life sentences in 2020 exceeded the total prison population in 1970. “The unwillingness to scale back extreme sentences is at odds with evidence that long sentences incapacitate older people who pose little public safety threat, produce limited deterrent effects, and detract from more effective investments in public safety.”).

Ghandnoosh, N., Barry, C., & Trinka, L. (2023). One in Five: Racial Disparity in Imprisonment – Causes and Remedies. The Sentencing Project.

Komar, L., Nellis, A., & Budd, K. (2023). Counting Down: Paths to a 20-year Maximum Prison Sentence. The Sentencing Project.

Komar, Nellis, & Budd (2023), see note 5.

Komar, Nellis, & Budd (2023), see note 5.

Ghandnoosh, N. (2017). Delaying a Second Chance: The Declining Prospects for Parole on Life Sentences. The Sentencing Project. See also Reitz, R., & Rhine, E. (2015). Parole Release and Supervision: Critical Drivers of American Prison Policy. Annual Review of Criminology, 3, 283 (“From 1976 through 2000, 16 states and the federal system abolished parole-release discretion for most or all cases, making the actual length of judicially imposed prison terms more predictable or determinate—at least in theory.”

American Law Institute. (2017). Model Penal Code: Sentencing §305.6 – Modification of Long-Term Prison Sentences; Principles for Legislation, comment d.; See also Murray, J., Hecker, S., Skocpol, M., & Elkins, M. (2021). Second Look = Second Chance: Turning the Tide Through NACDL’s Model Second Look Legislation, Section III. National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

American Law Institute (2017), see note 9, comment a.

Love, M. C., & Klingele, C. (2011). First Thoughts About “Second Look” and Other Sentence Reduction Provisions of the Model Penal Code: Sentencing Revision, 42 U. Tol. L. Rev. 859, 868–69 (2011).

Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010); Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012).

California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Washington.

California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Ohio, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Tennessee, Washington, and Wyoming.

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 53a-39; Del. Code Ann. tit. 11, § 4204A; Md. Code Ann., Crim. Proc. § 8-110; Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 420A.203; Fla. Stat. Ann. § 921.1402; N.D. Cent. Code Ann. § 12.1-32-13.1; D.C. Code Ann. § 24-403.03.

Cal. Penal Code § 1170.91; N.Y. Crim. Proc. Law § 440.47.

18 U.S.C. § 3582(c); D.C. Code Ann. § 24-403.04.

Cal. Penal Code § 1172.1.

Cal. Penal Code § 1172.1; 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 5/122-9; Minn. Stat. Ann. § 609.133; Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 137.218; Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 36.27.130.

People v. Contreras, 411 P.3d 445 (Cal. 2018); Casiano v. Comm’r of Correction.,115 A.3d 1031 (Conn. 2015); Connecticut v. Riley, 110 A.3d 1205 (Conn. 2015); Peterson v. State, 193 So.3d 1034 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016); People v. Buffer, 137 N.E.3d 763 (Ill. 2019); State v. Lyle, 854 N.W.2d 378 (Iowa 2014); State v. Pearson, 836 N.W.2d 88 (Iowa 2013); State ex rel. Morgan v. Louisiana, 217 So.3d 266 (La. 2016); State v. Moore, 76 N.E.3d 1127 (Ohio 2016); McCullough v. State, 192 A.3d 695 (Md. 2018); People v. Stovall, 987 N.W.2d 85 (Mich. 2022); State ex rel. Carr v. Wallace, 527 S.W.3d 55 (Mo. 2017); State v. Comer, 266 A.3d 374 (N.J. 2022); State v. Kelliher, 873 S.E.2d 366, 389 (N.C. 2022); State v. Booker, 656 S.W.3d 49 (Tenn. 2022); State v. Haag, 495 P.3d 241 (Wash. App. 2021); Bear Cloud v. State, 334 P.3d 132 (Wyo. 2014).

Matter of Monschke, 482 P.3d 276 (Wash. 2021); People v. Parks, 987 N.W.2d 161 (Mich. 2022).

Commonwealth v. Mattis, 224 N.E.3d 410 (Mass. 2024).

Ghandnoosh, N. (2021). A Second Look at Injustice, p. 34. The Sentencing Project.

Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010); Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012).

Graham, 560 U.S. at 75.

Graham, 560 U.S. at 89-91, 119.

Those factors include considerations of a child’s chronological age and the hallmark features, including immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences; the family and home environment from which the youth cannot usually extricate themselves even if it is brutal or dysfunctional; the youth’s role in the crime; and the youth’s potential to become rehabilitated. Miller, 567 U.S. at 477.

Jones v. Mississippi, 593 U.S. 98 (2021). For more analysis, see Shapiro, D. M., & Gonnerman, M. (2021). To the States: Reflections on Jones v. Mississippi. Harv. L. Rev.: Vol. 135, Issue 1.

Annino, P., Rasmussen, D. W., & Rice, C. (2009). Juvenile Life Without Parole for Non-Homicide Offenses: Florida Compared to Nation. FSU College of Law, Public Law Research Paper No. 399.

Annino, Rasmussen, & Rice (2009), see note 29.

The Sentencing Project. (2019, October). Youth Sentenced to Life Imprisonment, p. 2 [Fact sheet].

Montgomery v. Louisiana, 577 U.S. 190 (2016).

Alaska does not have LWOP or JLWOP. Alaska’s sentencing scheme for homicide requires a mandatory 99-year sentence for certain first-degree murder provisions, and between a 5 – 99 year discretionary sentence for other similar offenses. Alaska Stat. Ann. § 12.55.125. Alaska has a modification provision for those serving mandatory 99-year sentences to apply for a review of sentence after serving ½ of that sentence.

Kan. Stat. Ann. § 21-6618; formerly Kan. Stat. Ann. § 21-4622 (2004).

Ky. Rev. State. Ann. § 640.040. See also Shepherd v. Commonwealth, 251 S.W.3d 309 (Ky. 2008); Beam, A. (2017, July 31). 4 in Kentucky seek new sentences for juvenile murder cases. The Associated Press.

Arkansas (2017); California (2017); Colorado (2016); Connecticut (2015); Delaware (2013); District of Columbia (2017); Hawaii (2014); Illinois (2023); Maryland (2021); Minnesota (2023); New Mexico (2023); Nevada (2015); New Jersey (2017); North Dakota (2017); Ohio (2021); Oregon (2019); South Dakota (2016); Texas (2013 & 2009); Utah (2016); Vermont (2015); Virginia (2020); West Virginia (2014); Wyoming (2013).

Diatchenko v. District Attorney, 466 Mass. 655 (Mass. 2013); State v. Sweet, 879 N.W.2d 811 (Iowa, 2016); State v. Bassett, 428 P.3d 343 (Wash. 2018).

Cal. Penal Code § 1170 (d)(1)(A); Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 16-13-1002.

People v. Buffer, 137 N.E.3d 763 (Ill. 2019). See also People v. Reyes, 63 N.E.3d 884 (Ill. 2016) (consecutive sentences totaling 97 years, requiring Reyes to serve a minimum of 89 years, was unconstitutional). See also People v. Ruiz, 197 N.E.3d 726 (Ill. Ct. App. 2023) (50 years for murder and 30 years consecutive for attempted murder were unconstitutional).

State v. Booker, 656 S.W.3d 49 (Tenn. 2022).

Booker, 656 S.W.3d at 68.

State ex rel. Carr v. Wallace, 527 S.W.3d 55 (Mo. 2017).

Casiano v. Comm’r of Correction,115 A.3d 1031 (Conn. 2015); Connecticut v. Riley, 110 A.3d 1205 (Conn. 2015).

Bear Cloud v. State, 334 P.3d 132 (Wyo. 2014). See also Wolfe, A. J. (2017). A Denial of Hope: Bear Cloud III and the Aggregate Sentencing of Juveniles; Bear Cloud v. State, 2014 WY 113, 334 P.3d 132 (Wyo. 2014). Wyo. L. Rev.: Vol. 17: No. 2, Article 6.

People v. Contreras, 411 P.3d 445 (Cal. 2018).

McCullough v. State, 192 A.3d 695 (Md. 2018).

State v. Moore, 76 N.E.3d 1127 (Ohio 2016).

State ex rel. Morgan v. Louisiana, 217 So.3d 266 (La. 2016).

Peterson v. State, 193 So.3d 1034 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016).

Morgan, 217 So.3d at 277.

For a comprehensive overview of the cruel and unusual provisions in state constitutions, see Berry, W. (2020). Cruel State Punishments. N.C.L Rev., 1201-1254.

State v. Kelliher, 873 S.E.2d 366, 389 (N.C. 2022).

Kelliher, 873 S.E.2d at 382.

Kelliher, 873 S.E.2d at 366. In a companion case, North Carolina also held that life sentences with parole, while not guaranteed parole at any point, must have the opportunity to seek early release after serving more than 40 years. State v. Conner, 873 S.E.2d 339 (N.C. 2022). See also Finholt, B. (2023). Toward Mercy: Excessive Sentencing and the Untapped Power of North Carolina’s Constitution. Elon L. Rev. (forthcoming), Duke Law School Public Law and Legal Theory Series No. 2023-55.

People v. Stovall, 987 N.W.2d 85 (Mich. 2022).

State v. Haag, 495 P.3d 241 (Wash. App. 2021). But see Washington v. Anderson, 516 P.3d 1213 (Wash. 2022) (a sentence of 61 years was not a de facto life sentence because Haag did not show that his crimes reflected youthful immaturity, impetuosity, or failure to appreciate risks.

State v. Comer, 266 A.3d 374, 388 (N.J. 2022).

Comer, 266 A.3d at 388.

State v. Lyle, 854 N.W.2d 378 (Iowa 2014).