Having highly qualified, effective teachers in our nation’s classrooms matters. This fact is difficult to refute, even given other influences on public schools such as poverty, class size, family struggles, mental health, violence, and lack of funding. However, evaluating teachers and teaching is an imperfect proposition at best, and one we’ve been struggling with for well over two centuries. Gaining a foothold on the foundations of teacher evaluation – WHY we evaluate teachers, WHAT constitutes teacher quality and quality teaching, and HOW we can effectively implement good teacher evaluation systems – can help us improve this critically important aspect of education and ensure our classrooms are staffed with the best.

First, teacher quality is positively linked with student learning. This is the primary reason to develop, implement, and continue our efforts to improve teacher evaluation systems. As a nation the US has historically struggled to come to a consensus about what constitutes “teacher quality” and how exactly to define it. Early 19th century teachers were considered effective if they taught the curriculum chosen by community leaders, if they sustained proper discipline with children, and if they maintained the physical premises of the school and classroom.

Today when we speak of teacher quality, we consider factors such as:

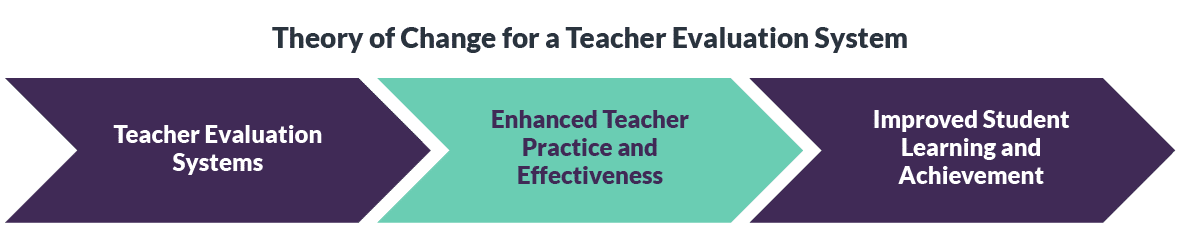

A secondary reason for sound teacher evaluation systems is accountability. The expectation is that the evaluation process itself will enhance teacher practice and improve effectiveness, and this in turn will lead to improved student learning and achievement. In some cases, teacher evaluation systems have led to improvements in the teacher workforce. “When properly implemented, evaluation reforms can dramatically improve teacher quality, build trust with teachers, and contribute to improving other a host of educational institutions, such as teacher preparation programs.” However, “properly implemented” is easier said than done, especially given the multitude of responsibilities and demands on both teacher and administrator time.

Prominent educational researcher John Hattie is best known for his meta-analyses of dozens of influences on student learning. Hattie ranked these influences according to “effect size,” and found that collective teacher efficacy ranks highest on the most recent iteration of the list. Other key influences on Hattie’s list related to teacher quality include teacher credibility at .9, and teacher clarity at .75. These three teacher-related influences rank higher than more than 200 other influences studied, including factors educators have typically blamed for poor student performance:

Many of our nation’s schools are grappling with issues of educational equity, making efforts to ensure that our students, no matter their personal and family characteristics, have both the access and the opportunity to achieve at high levels. However, when we address educational equity, our focus is typically on student demographics – race and ethnicity, socio-economic status, disability status, and whether students are English Language Learners. We offer teachers professional development to increase their understanding of equity through the lens of how structural and institutional racism and other forms of discrimination impact students. Rarely, however, do we make an explicit connection between issues of equity and teacher quality.

In 2012, Students Matter, a non-profit organization that uses litigation to fight for access to quality public education, filed one of several lawsuits on behalf of students in California addressing the issue of teacher quality from the perspective of equity and access. They claimed that the California Education Code’s provisions for teacher tenure and dismissal were unconstitutional, as they “denied students equal protection by perpetuating a system that negatively impacted students unlucky enough to be placed in a classroom with a ‘grossly ineffective’ teacher.”

The court initially found persuasive that ‘a single year in a classroom with a grossly ineffective teacher costs students $1.4 million in lifetime earnings per classroom.’ Experts testifying in the case further stated that … students taught by teachers ranking ‘in the bottom 5 [percent] of competence lose 9.54 months of learning in a single year.’

Expert testimony included results from a key study on teacher quality and impact on students using Value-added Models (VAM), a way of statistically isolating and analyzing a teacher’s contribution to student learning. Students Matter initially prevailed in Superior Court, but the case was eventually overturned by the California Court of Appeal. Still, evidence presented in the case along with its initial success are an important part of the history and are vital to understanding and defining quality teaching and fairly evaluating teachers.

The Students Matter case was hardly the first to consider teacher quality as it pertains to educational equity. In 1966, James S. Coleman issued a groundbreaking report on educational opportunities for minority students and in it identified that in comparison to factors such as school facilities and curriculum, the quality of teachers shows a stronger relationship to pupil achievement. Furthermore, it is progressively greater at higher grades, indicating a cumulative impact of the qualities of teachers in a school on the pupil’s achievements. Again, teacher quality seems more important to minority achievement than to that of the majority.

If we want equitable schools for all students, we must ensure there is quality teaching taking place in every classroom.

Other resources you might like:

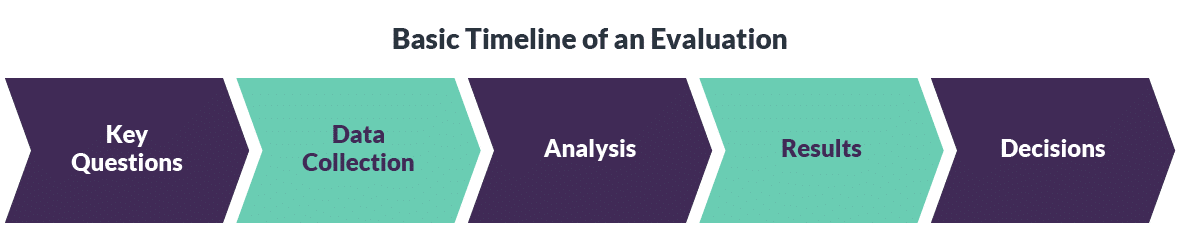

To define teacher evaluation, we first have to understand evaluation. At its core, any kind of evaluation – whether we are evaluating a person, a program, a process, a product, or even a policy – is ultimately a judgement, appraisal, or assessment. Evaluation is typically based on one or more key questions the evaluator needs to pursue, and the collection and analysis of relevant data to help answer those questions. Results derived from the data then are used to inform decisions.

We engage in random acts of evaluation every day. We evaluate weather conditions to inform clothing choices, we gather data on products to inform purchase decisions, and we assess hunger levels and take stock of refrigerator contents to inform meal planning. More formal evaluation efforts, such as program or product evaluation, include systematic data collection and analysis through tools such as surveys, interviews, and observations that help determine the quality, value, and importance of the program or product.

Underpinning evaluation are the broad questions that drive data collection. For teacher evaluation, as for any type of employee evaluation or performance review, we begin with (often implicit) questions such as “How effective is this person’s practice?” or “To what extent is this person meeting the criteria for success in this position?” But to answer questions about “effectiveness” or “success,” we must know what we mean by those terms. We have to operationalize, or clearly define and describe them. We say we want high quality teachers in our classrooms, but what are we looking for when observe them?

One of the key challenges in any system of teacher evaluation is the need for stakeholders (including teachers and administrators) to agree on what exactly constitutes “good” or “effective” teaching. Researchers have labored for more than a century over definitions, descriptions, frameworks, and rubrics (many of these current tools are abundant in the marketplace) to differentiate poor from mediocre from exemplary teaching – the main purpose of a good evaluation system. Current evaluation systems in school districts generally rely on one or more of these products, chosen at times through a collaborative effort between both teachers and administrators.

While the tools used by a particular school or district tend to vary in specific wording and scope, many include a common collection of effective teaching characteristics. A 2013 review of international literature on effective teaching resulted in the following list. Effective teachers:

This study goes on to say that “…good subject knowledge is a prerequisite. Also, the skillful use of well-chosen questions to engage and challenge learners… [and] the effective use of assessment for learning” are necessary for good teaching.

This point about common language around effective teaching is no small matter and is, in fact, a linchpin in the strength and validity of a teacher evaluation system. Reaching language consensus around effective teaching opens the door to meaningful and useful feedback, another mainspring of a robust evaluation system.

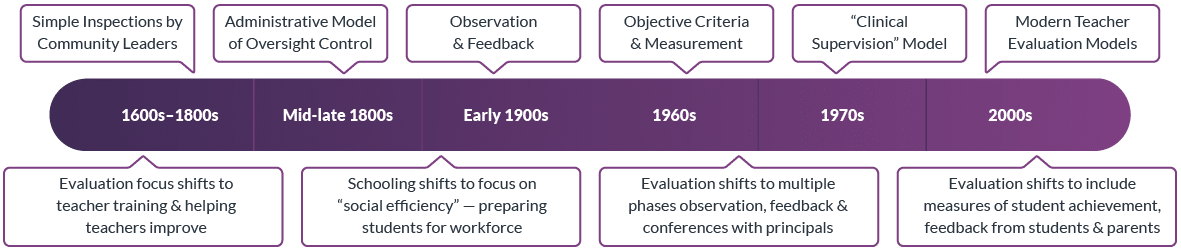

Teacher evaluation is as old as public schooling itself. Early accountability systems were comprised of no more than simple inspections of whether teachers were doing what was expected of them, without specific regard for student learning or achievement. When public schools shifted to an administrative as opposed to a community model of oversight and control in the mid- to late 19th century, leaders began to pay more attention to teacher training and helping teachers improve their practice.

Soon after, observation and feedback became regular features of evaluation models. “The first program evaluator, Cyrus Pierce, stated, ‘I comment upon what I have seen and heard… , telling them what I deem good, and what faulty, either in their doctrine or their practice, their theory or their manner.’”

Public schooling exploded in the earliest days of the 20th century with an immigration boom in full swing. At the same time, the US experienced rapid growth of urban areas, expanded compulsory education, the introduction of child labor laws, unparalleled technological advances, and an ever-changing American cultural landscape. Educational leaders at this time began to rethink the purpose of schooling as it shifted from child-centered individualized education to social efficiency – preparing all students to be good citizens and good workers. Along with the growth of schools came multiple layers of administration and bureaucracy and need for standardization. All of this influenced changes in curriculum, teaching practices, and ultimately, teacher evaluation.

Between 1900 and 1920, it was proposed that teaching could be measured and made more efficient using successful business productivity methods. This concept shifted teacher evaluation away from an inspection model toward increased teacher observation and the development of objective criteria to measure performance. Even though business productivity models influenced the emerging teacher evaluation model, supervisors and principals remained the tools of carrying evaluations out; their ability to assess performance accurately was presumed.

As models moved from inspection to assessment against a set of criteria, there evolved more emphasis on collaboration between teachers and principals, with a focus on instructional improvement rather than dismissal. Partnerships and relationships were prioritized with the expectation that this would naturally increase teachers’ investment in their work and thus lead to better teaching and positive student outcomes. However, in the post-Sputnik era that saw increased federal influence on public education and expanded interest in scientific approaches, this shifted back to an emphasis on objective criteria and measurement using multiple sources of data. And educators soon realized again that “evaluation policies based on principles of economics and corporate management [had] failed to take into account the complex and personalized work of educating students.”

By the 1970s teacher evaluation incorporated the now familiar “clinical supervision” model, a “multiphase process that required the supervisor and the teacher to plan, observe, analyze, and discuss the teacher’s ‘professional practice.’” Modern-day teacher evaluation systems that emerged from this model continue to vary among the states, but most share a couple of common elements:

The use of standardized test scores, though now quite common, is still somewhat controversial. Experts recommend careful consideration for how achievement scores are used and weighted, and advise always using multiple measures to assess overall teacher quality.

Student achievement can be, indeed, should be, an important source of feedback on the effectiveness of schools, administrators, and teachers. The challenge for educators and policy makers is to make certain that student achievement is placed in the broader context of what teachers and schools are accomplishing.

Some evaluation systems also include student or parent perception surveys, and others may include project-based alternatives to observation such as action research. Most systems result in some sort of composite score and overall rating. These types of modern systems arose in the early and mid-2010s amid significant political pressures and challenges with implementing them at state and local levels. By 2015, 45 US states required some sort of annual evaluation for all new non-tenured teachers and over half of states require an annual evaluation for all teachers. These new systems were designed to give school leaders the ability to differentiate among teachers on factors related to student outcomes as opposed to simply rating teacher effectiveness in isolation. The expectation was that they would revolutionize the way teachers were hired and fired.

Many teacher evaluation systems rely on a large set of “indicators” – detailed descriptions of what effective teaching should look like at different levels of proficiency (e.g., ineffective, developing, effective, highly effective ) across various domains such as lesson planning, content knowledge, instructional practices, classroom environment, assessment, professional development, and collaboration. Indicators may be aligned with state standards for teaching practice.

It is easy to identify a set of common challenges with teacher evaluation systems. After all, they’re perennially rife with controversy, pitting administrators and teachers’ unions against each other amid various local and federal political pressures endemic to public education.

Validity.Many people both inside and outside of education question whether current systems are valid or whether they work at all to ensure effective teaching. After all, principals may see as little as 0.1% of instruction if they observe one teaching period per year based on 5 periods per day and 180 school days a year. Bump that to observing 3 periods per year and that’s still only 0.3% of teaching, leaving many to wonder, what happens in the classroom the other 99.7% of the time?

Many teachers confess to putting on the “snapshot lesson,” also known as the “dog-and-pony” show when the principal comes into the room. Principals may even hear multiple complaints about a teacher from parents, students, and colleagues over the course of a school year, but when they enter the classroom to conduct the observation, they find a well-managed class with a perfectly executed lesson in place. Couple this with a lack of specific, meaningful and actionable feedback from administrators and it leaves teachers feeling as if evaluation doesn’t count for much outside of the summative rating they receive that puts their minds at ease (or perhaps causes undue stress) until the next cycle. When they do seek assistance, “where do teachers go for helpful feedback on their teaching? Usually they turn to a colleague, a spouse, a family member, students, parents — or nobody.”

It is highly doubtful many people in or outside of education believe that the one-off observations alone paint a sufficient and robust picture of a teacher’s capabilities, even when they are paired with student achievement scores.

Trust and privacy.Concerns about trust between teachers and administrators is perennial and pervasive. Teachers’ unions are often at odds with administration, and tensions are even higher in the months (and sometimes years) when contract negotiations are underway. Privacy concerns around individual teacher evaluation data became a real concern in recent years, peaking in 2010 when The Los Angeles Times famously sued the Los Angeles Unified School District for access to teacher names and evaluation results. The Times argued that the public had a strong interest in teacher ratings, but (in an apparent win for teachers) an appellate court panel found a stronger interest in keeping names confidential, especially given the impact publishing them would have likely had on teacher retention and recruitment.

Equity.Evaluation systems are also questioned with regard to equity among teachers of different levels, subjects and special areas. Is it fair and just to evaluate kindergarten, chemistry, and physical education teachers using the same indicators and measurement tools? Can we effectively articulate quality criteria for all teachers in all types of classrooms at all levels? Should standardized test scores be used to evaluate all teachers? Many (but certainly not all) think we already have these answers, in the extant frameworks and rubrics currently used across the nation.

The “widget effect” and “failure to launch.”In some places, nearly all teachers are rated “effective” or “satisfactory,” if not even higher. Compounding those results:

The mentor teacher asked her novice, a 3rd year teacher, about a recent observation by the school principal. “How did it go?” the mentor inquired. “OK, I think,” the new teacher shrugged as if this was just a guess. “What feedback did you get from your principal?” the mentor probed. “I don’t know” she mumbled as she turned her attention back to arranging a stack of student papers. “I haven’t looked to see if he put anything in the [online] system. He doesn’t usually say much.”

Time.Principals, like teachers, are frequently overwhelmed by the ever-growing demands of their jobs. Accountability requirements, instructional and behavioral challenges, and all of the proverbial “administrivia” get in the way of them doing what they often know is the meaningful work, including providing feedback to teachers. Even when administrators are well-trained in the tools and frameworks of evaluation system, have expertise in the content areas, and have years of experience or other qualifications that in theory should make them good evaluators, they are often held back by the limits of the evaluation systems themselves, as well as the perennial challenges of time and competing priorities and responsibilities in education.

…Principals have little choice but to focus on teaching performances versus learning results, on chalkboard razzledazzle versus deep understanding, on beautiful bulletin boards versus demonstrated proficiency. Constrained by the supervision/evaluation process, principals overmanage the occasional lesson and undermanage the bigger picture of whether teachers are truly making a difference in student learning.

Of course, demands on both administrator and teacher time seem to inexplicably increase each school year, leaving the task of prioritizing responsibilities harder and harder to manage. And teacher evaluation done well is undeniably a time-intensive pursuit.

Successful models of teacher evaluation are those that lead to improvement in instructional practice, improvement in measures of student learning and achievement, and improvement in the retention of effective teachers and improvement of lower-performing teachers. The landmark Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) project, a multi-year study funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation designed to investigate and promote great teaching, concluded that “evaluation systems that include both value-added calculations and other factors, including classroom observation and student surveys, are the most stable measures of teacher quality.”

Effective models engender the conditions for collaboration among administrators and teachers, and create space for administrators to provide meaningful and actionable feedback for teachers, rather than just a simple summative rating. They come with opportunities for principals (and other supervisors) to get high quality, adequate, and ongoing training in how to understand and use the elements of the model (e.g., standards, rubrics, data collection tools). They advance (or at least do not detract from) a culture of continuous learning, and open dialogue around teaching successes, challenges, and opportunities for growth. Effective models are connected to specific opportunities for professional growth in the areas identified through observation and other measures and through additional evidence of classroom practice and student learning.

A 2018 report by the National Council on Teacher Quality describes case studies of successful teacher evaluation systems in school districts in six different states and in them found a set of core principles responsible for their success:

Their success was also strongly linked with “a thoughtful approach to weighting individual evaluation components” as well as key personnel and compensation decisions. Worth noting too, is that at the time of the report, in five of the six districts studied, the evaluation system maintained its adherence to core principles despite changes in leadership (one superintendent was still in place).

Strong teacher evaluation systems, when paired with supports and incentives, are designed to do the following: 1) Provide a more valid measure of teacher quality by distinguishing between teachers at different performance levels; 2) Recognize strong teachers and keep them in the classroom; 3) Encourage consistently less effective teachers to leave the classroom; 4) Help all teachers improve; 5) Recruit more effective new teachers; and 6) Achieve gains in student learning and other positive student outcomes. School leaders (along with teachers) need to understand the purpose of evaluation as a “coherent, comprehensive, and coordinated approach to improving teaching quality” and also as a part of a larger interconnected and complex system focused on reaching, teaching, and supporting all students in constant pursuit of continuous improvement.

…teacher engagement throughout the design and development process is not merely beneficial but critical to success. Teachers, as the experts in their craft, have much to contribute to the design and implementation of teacher evaluation systems. Their engagement throughout the process promotes ownership and efficacy of the system. These systems are more likely to produce the results we desire—improved teaching quality and increased student learning—when teachers believe the systems and approaches will help them be more effective with their students.

Teacher evaluation is a necessary component of a successful school system, and research supports the fact that “good teachers create substantial economic value.” Ensuring teacher quality with a robust, fair, research-based, and well-implemented teacher evaluation system can strengthen the teacher workforce and improve results for students. Our students don’t use the same frameworks and tools as school leaders to evaluate teachers, but they certainly know good teaching when they experience it -and they’re fully aware of it when they don’t.

About Sheila B. Robinson

Sheila B. Robinson, Ed.D of Custom Professional Learning, LLC, is an educational consultant and program evaluator with a passion for professional learning. She designs and facilitates professional learning courses on program evaluation, survey design, data visualization, and presentation design. She blogs about education, professional learning, and program evaluation at www.sheilabrobinson.com. Sheila spent her 31 year public school career as a special education teacher, instructional mentor, transition specialist, grant coordinator, and program evaluator. She is an active American Evaluation Association member where she is Lead Curator and content writer for their daily blog on program evaluation, and is Coordinator of the Potent Presentations Initiative. Sheila has taught graduate courses on program evaluation and professional development design and evaluation at the University of Rochester Warner School of Education where she received her doctorate in Educational Leadership and Program Evaluation Certificate. Her book, Designing Quality Survey Questions was published by Sage Publications in 2018.

We know that figuring out how to begin can often be the hardest step. We can help.